On Archaeology

Wonne Ickx

Architectural Review Asia Pacific, No. 135 (AR 135), 'Elements', June 2014

In an article written for Mexico City-based architecture magazine, Arquine, entitled ‘La Edad del Barro’, roughly translated into English as ‘The Mud Age’, certain questions were raised as to current developments in contemporary architecture – perhaps more notable in Latin America and more peripheral regions of the globe – in which a search for a certain vernacular kinship is the driving force behind architectural design.

The article espoused certain materials and textures as recently reappearing as radically different to the more ‘innovative’ components dominating the architectural market in recent decades. In industry-specific magazines, natural timber, rammed earth, adobe, cement blocks and handmade ceramic tiles have gradually been replacing the bend Corian surfaces, smooth epoxy floors or sophisticated multi-perforated metals, which were seen as so ‘innovative’ only yesterday. Textiles, rustic assemblies, ancient timber techniques and an ethic of doing-more-with-less has, more recently, replaced laser-cutting, CNC milling and complex digital fabrications, shifting the gaze from technology to craftsmanship. The descriptions of projects are illustrated with awkward specifications that seem to come out of archaeology books or even local oral tradition: Mexican architects proudly describe their whitewashed walls with a mixture of chalk and cactus dribble, mesquite wood beams or traditional palm roofs that make up their projects. Nothing seems more fashionable than to mimic indigenous traditions, using bygone techniques and primitive constructive simplicity. This interest in a local low-tech aesthetic has not only generated a different architecture but has also changed the geographical focus. Leaving London, New York, Tokyo and Singapore aside, no place seems too far away now to house contemporary architecture: the 60th edition of the Mexican journal Arquine, as a mere example, reported projects in areas such as Temascaltepec and San Luis Potosi (Mexico), Kigali (Rwanda) and Curicó (Chile). This seems to suggest a shift in focus from global cities to rural areas of distant countries.

The elemental, primitive, basic, natural, honest, vernacular, traditional, indigenous or even precarious are defining concepts that have become a common refuge to protect architects from the allegations that have been inflicted upon them in recent years: to be egocentric individuals delivering mere visual spectacle. The optimistic and festive trends of past decades, is being gradually invaded by a melancholy for an ‘invented past’: a search for a simple, straightforward architecture that belongs to the territories and landscapes forgotten by globalisation. In an attempt to turn its back on a recent past full of formal excesses and expensive extravagances, architecture is once again content with a celebration of straightforward simplicity, filling magazines and blogs with timber-lattice structures and adobe brick walls. Replacing the hyper-sophisticated metal meshes for compacted soil in order to celebrate the elegance of what-always-was.

A far too often superficial search for ‘authenticity’ raises fundamental questions, which can be easily related to the comments of Jean Baudrillard in his book System of Objects (Radical Thinkers) (1968) when he discusses the rebuilding of an old country house in France: ‘Rather as a church does not become a genuinely sacred place until a few bones or relics have been enshrined in it, so this architect cannot feel at home … until he can sense the infinitesimal yet sublime presence within his brand-new walls of an old stone that bears witness to past generations.’ Although this nostalgia for the past and an obsession for authenticity might be a mere wave of formalism reacting against previous excesses (blending in perfectly with updated concepts from the late sixties and seventies regarding sustainability, community-based design and vernacular concerns), there is a particular part of this ‘looking-back-to-the-past’ that demands attention.

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago recently published a book called The Way of the Shovel: Art as Archaeology (2013), which explores the ‘archaeological imaginary in art’. The book, published as part of an exhibition organised by senior curator, Dieter Roelstraete, examines the recent attention in contemporary art towards the past. ‘One of the defining ironies of our time,’ he writes, ‘is that so much of the vanguard of the production – the art that is most closely aligned with the boundary-pushing, experiment-prone, horizon-expanding tradition of progressive culture and with the avant-garde’s traditional claim to newness in particular – should be so preoccupied, both in its choice of techniques, in both form and content, with the old, the out-dated, the outmoded – with the past. In other words, still: it is one of the defining ironies of our time that the one sector of culture most commonly associated with looking forward should appear so consumed by a passion for not just looking the proverbial other way but in the opposite direction - backward.’ (‘The Way of the Shovel, On the Archaeological Imaginary in Art’, p15-16, 2013)

Ancient ruins, excavation sites and pre-modern constructions have always had a special place in the architectural imaginary at Productora. When browsing through books of the excavated churches in Ethiopia, earth Mosques in Mali, step wells in India or the adobe constructions in Peru, there is a specific quality of architectural information present that seems to ignore ideologies, personal histories and authorship. It is not the scientific-historic ambition to make these silent remains speak again that is of relevance here. It is the appreciation for the archaeology of architecture – also of archaeology as such – and has to do with the very simple fact that this specific discipline (which is, just like architecture, simultaneously a science and a humanity) focuses on the physical presence of objects. Archaeology – defined in dictionaries as ‘the study of material culture’ – is also more relevant for pre-history than for history, since the advent of recorded chronicles have displaced, to a large extent, this urgency of matter. If considering the elemental part of archaeology, the excavation or the ‘dig’ (leaving the speculative interpretations momentarily out of the question), the observer is simply confronted with the disclosure of objects scattered in space. A numeric three-dimensional account of items located in the earth’s crust. Archaeology, in the first instance, is history without words, buildings without rhetoric, space without program. It is architecture as mere matter, retained in a three-dimensional matrix of dirt.

While architectural history narrates intentions and ideologies of its creators (the architects and their societies), the archaeological dig simply uncovers the building itself. The structures appear as a bare-stripped rhythm of elements, such as walls, columns, chambers, plazas, patios and porticos; a mute mass of material that marks the territory and divides space in smaller fragments. The quintessential beauty of excavation sites is that time has eroded all the superficial excesses and that only the sum and substance of the architectural proposal is presented to us: a pristine conceptual blueprint. Over long spans of time, layers of architectonic information have been annihilated: the inhabitants left, pots are broken, tapestries and wooden shelves dissolved through organic breakdown, finishing, stucco and painting slowly eroded, interior walls collapsed and the structure crumbled down slowly over the foundations buried in the earth. The architecture is dismantled in the reverse order of its construction: separating solid from delicate, structure from infill, soft from hard, plan from section, element from element and spatial layout from decoration. Whatever came last disappears first.

The visual resemblance between a fresh building site and an archaeological dig is indeed striking: while the former advances quickly, leaving the horizon and erecting upwards, the latter goes slowly and meticulously downwards, digging deeper and deeper. In both cases however, the foundations – recently built or just uncovered – show the DNA of the building: its measurements, thickness, bay widths, repetitions, centrality or centrifugality, its adaptation or stubborn resistance to the geography, its orientation, hierarchy, texture, scale and morphology. The excavation escapes cunningly the question of the facade, it ignores the images of the building. The clear-cut geometries of many settlements unearthed at archaeological sites are structures reduced to an initial parti sketch. As if they were somebody´s first lines on paper, they are condensed to a mere spatial layout over territory; a last testimony that evokes the original intention. The initial lines in the sand and the building’s last remains overlap miraculously through time and media. Disregarding the weak information, the circumstantial concerns, the programmatic flotsam and jetsam, the softness of decoration, as well as the coming and going of inhabitants, the architecture remains immutably present.

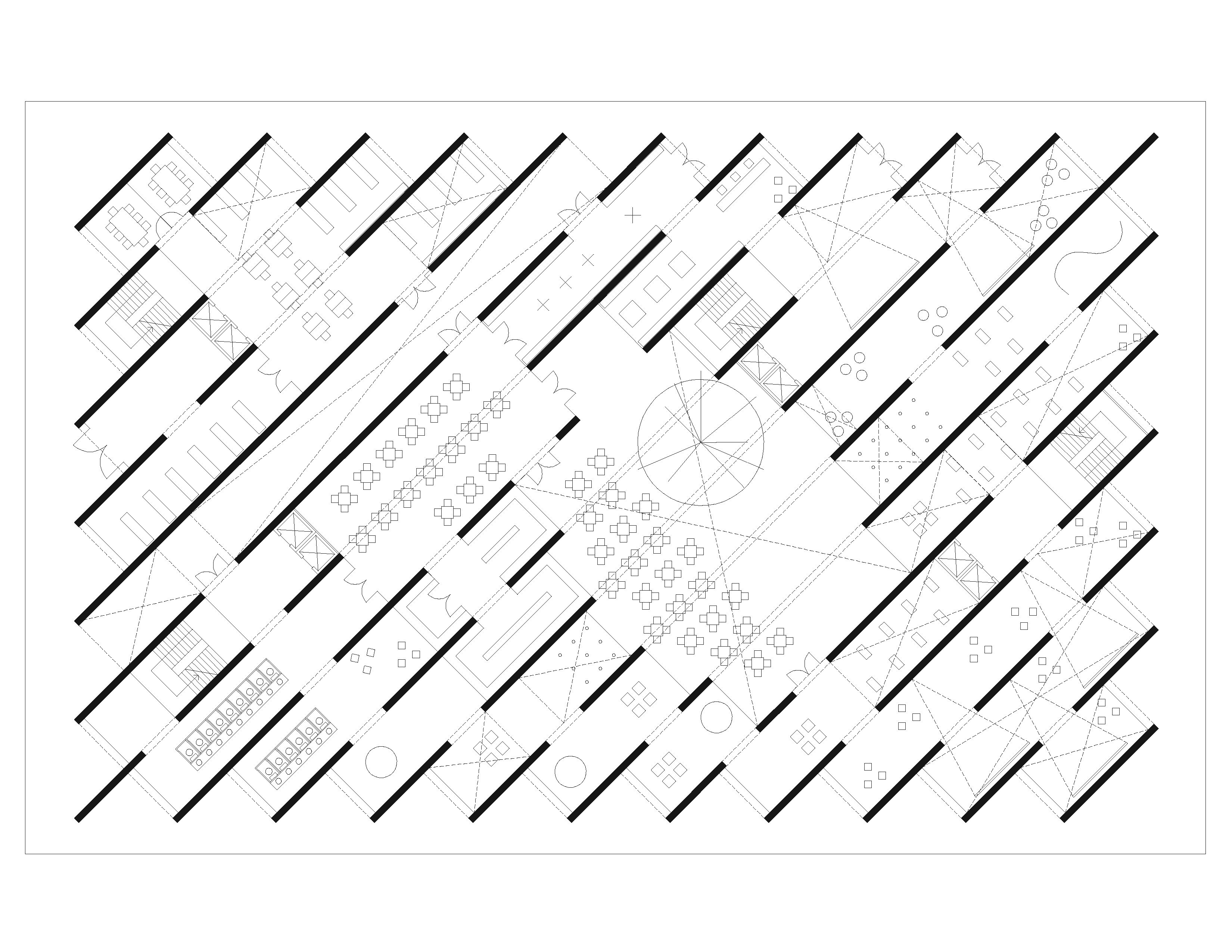

Image:

Illustration from PRODUCTORA, Mexican Pavilion, Shanghai, 2010

View Project: Mexican Pavilion