Empty Catalogues

Wonne Ickx

LIGA /Exposed Architecture, Park Books, 2017

In recent years an unprecedented interest in the study of architecture exhibitions has emerged. Whole issues of magazines and books have been dedicated to the subject, international congresses have been organized and more and more institutions offer masters degrees or diplomas that establish crossovers between architecture and exhibition making.

Simultaneously scholars, museum directors and curators have enthusiastically highlighted the importance of exhibitions in shaping architectural history.[1] In recent decades, curating and exhibiting architecture has indeed become a discipline in itself.

Architectural historian Eve Blau wrote the following on the specific nature of architecture exhibitions: “Information and ideas about architecture are presented and elucidated very differently in the space of the exhibition gallery than they are in the written text of a book. This is not only because the exhibition relies more heavily on images than on words, but because it presents its subject visually and constructs its arguments spatially—by assembly rather than explication, and through relationships of proximity, juxtaposition, contingency, estrangement, and so on, that are essentially spatial.”[2]

Studying past architecture exhibitions adequately is therefore not an easy task. It is especially hard to piece together the spatial characteristics of former architecture exhibitions: there is a general scarcity of photographs of general exhibition views, floor plans and elevations of past exhibition projects. Let alone some kind of record of sound, light and multimedia installations. If we believe that exhibitions are indeed more than just spatialised books, getting an idea of the spaces, routes, perspectives and exhibition design experiences visitors were undergoing, is crucial to understanding the essence of past exhibitions. A good starting point—we might think— would be to consult the official documentation of the event: the catalogue. Unfortunately, exhibition catalogues in general do not take us any further than a factual overview of the exhibited content, an introduction by the curator and some additional essays or observations.

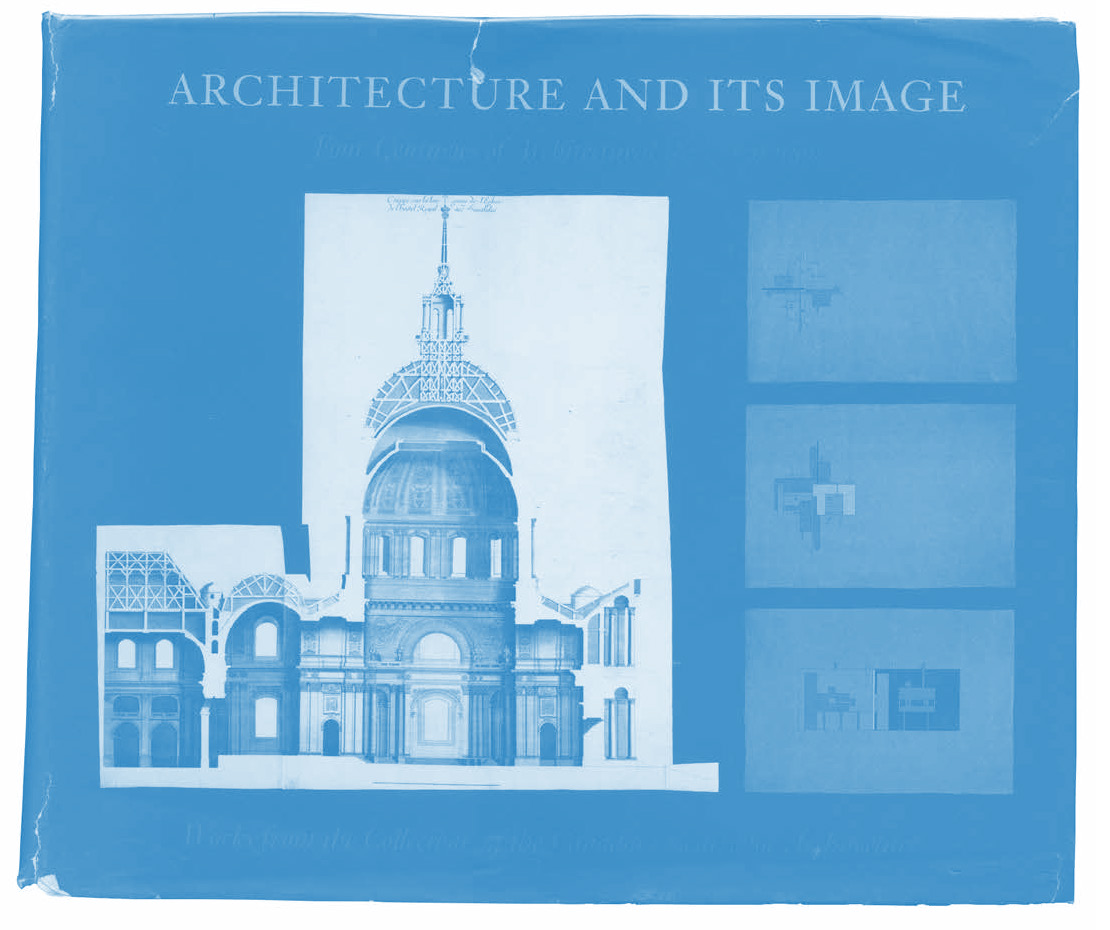

To pick out just one example I have at hand on my bookshelf: the weighty catalogue published in 1989 to accompany the ambitious exhibition “Architecture and Its Image”[3] by the Canadian Center for Architecture (CCA). The exhibition was presented to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the institution and the opening of the CCA’s newly built venue. The 370-page catalogue starts off with a series of lengthy essays and then continues into a second part—“The Catalogue” proper—that depicts the artifacts, drawings and images of the exhibition, neatly divided into the three same chapters that constitute the show. Even though this catalogue and exhibition are coincidentally also by Eve Blau, in collaboration with Edward Kaufman, there is absolutely no trace in the extensive volume of the above-mentioned “visual experience and spatial arguments.” The catalogue is here simply reproducing its etymological essence: a kata-logos or “complete count,” a list, a register.

Catalogues—the enduring counterpart of the ephemeral architecture exhibition—do indeed fall short if we wish to reconstruct the essentially spatial relationships of proximity, juxtaposition, contingency and estrangement explained by Blau. As a starting point there is the practical problem that many comprehensive catalogues are planned to be printed and bound ready for distribution by the day the exhibition opens, and therefore simply cannot include photographs of the finished exhibition rooms. To allow for a certain flexibility in the exhibition mounting and last minute changes, catalogues rarely provide spatial information such as plans, elevations or detailed aspects of the exhibition design. If we are lucky we can find these drawings briefly mentioned in a monograph on the architect or designer in charge. In the best-case scenario we would be able to piece together a spatial map of these exhibition by combining these different sources of images, drawings and text, but in general reconstructing the spatial layout of past exhibitions is a hard nut to crack. Studying exhibitions through their catalogues most closely resembles analyzing a movie without seeing the film.

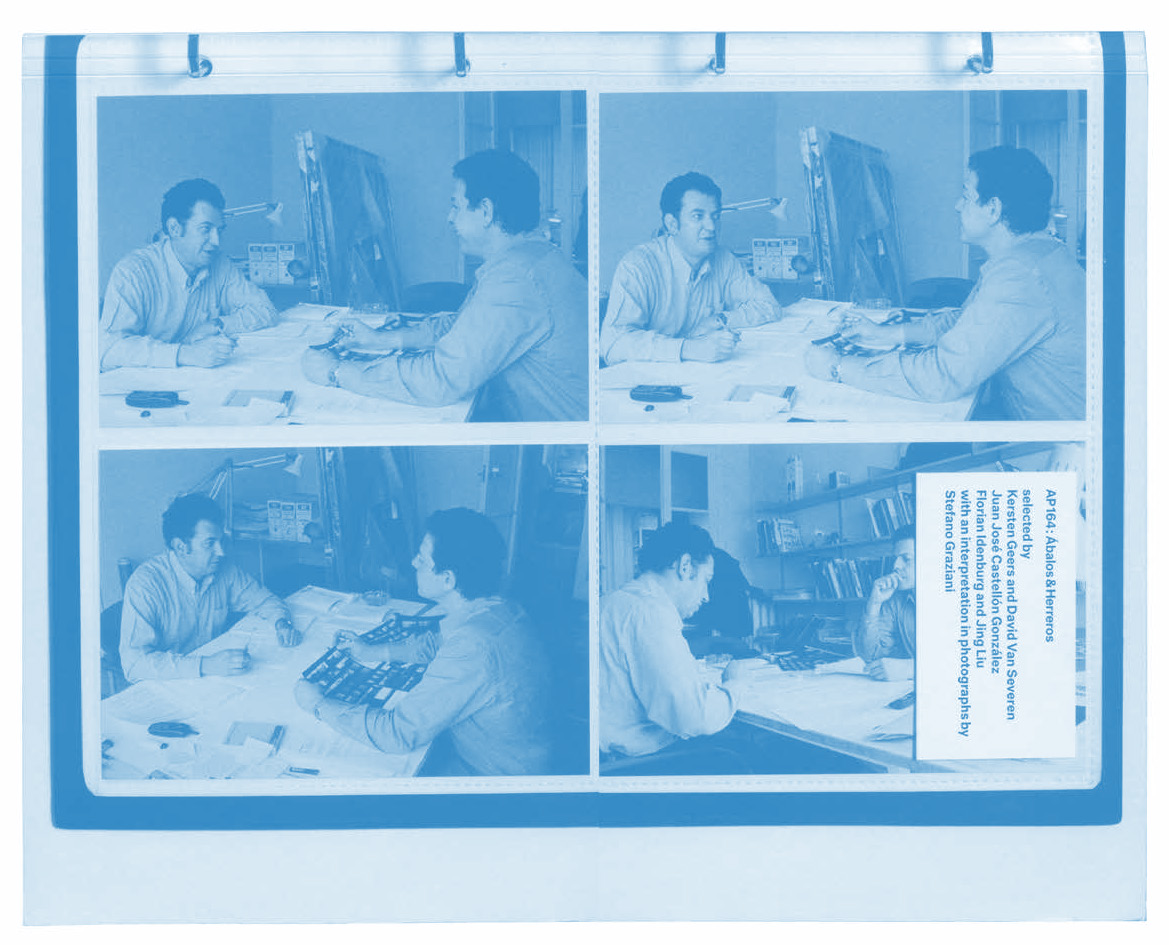

Contemporary exhibition catalogues seem to have understood this problem. If we take for example—as a counterpart to the previous case— the latest catalogue by the CCA I have on my work desk, we notice a completely different approach. The book AP164: Ábalos & Herreros [4] is a catalogue documenting three small consecutive exhibitions based on the archives of Iñaki Ábalos and Juan Herreros, which were recently donated to the CCA. It forms part of the “Out of the Box Series,” an ongoing project of the CCA in which new material acquired by the institution is presented to the public by means of an open research project, collapsing the notions of cataloguing, investigation and exhibition into one single gesture. In this case it is Giovanna Borassi who leads the process and selects three curatorial teams (Office KGDVS, Juan José Castellon and SO-IL) to examine the new material. Without going too much into the exhibition format or specific curatorial proposals, we can observe noticeable changes in the content and structure of the exhibition catalogue. For instance, the spatial layout of the exhibition plays a fundamental role: the octagonal exhibition room in which the exhibition took place is carefully portrayed, starting with a shot of the entrance sequence. These exhibition views are the only images printed full spread in the book, illustrating the importance of the spatial experience of the exhibition. In the case of SO-IL there is even a detailed drawing of the carpet pattern they designed for the exhibition. Secondly, the curators appear: adorned with white gloves, they bend over their laptops, retrieve objects from wooden crates, examine slides with magnifying glasses and listen to found playlists. The whole process (from the initial opening of boxes, folders and files to the moment when the subjects themselves—Iñaki Ábalos and Juan Herreros—visit the exhibition and participate in a round table discussion) is documented. Even the photographer is photographed.

Although the comparison is not completely justified—the two exhibitions have different subjects, ambitions and goals—it clearly illustrates a change in attitude towards conceptualizing, producing and documenting exhibitions through catalogues. It exemplifies a shift from the final “index of works” towards the process of exhibition making: from a concentrated attention on the indexation of primary matter towards the complete experience of the exhibition as research process. Contemporary exhibition catalogues, such as the one mentioned above, fill in the blanks left by traditional exhibition publications and recognize the importance of the exhibition as a spatial construct, stressing the need for them to be documented as such.

Notes:

[1] For example: “it is my contention that exhibitions, in the most diverse formats, have been vital instruments for advancing some of the greatest features of modern architecture since the Enlightenment, facilitating the emergence of a critical discourse on the public character and the responsibilities of architecture…” Barry Bergdoll, “Out of Site/In Plain View: On the Origins and Actuality of the Architecture Exhibition,” in Exhibiting Architecture: A Paradox? Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen (ed.), YSOA, New Haven, 2015, p. 14.

[2] Eve Blau, “Reviewing Architectural Exhibitions, Exhibiting Ideas,” JSAH, vol. 57 (Sept. 1998), nr. 3, p. 256.

[3] Eve Blau and Edward Kaufman (eds.), “Architecture and Its Image: Four Centuries of Architectural Representation,” Montreal and Cambridge, Mass., CCA/The MIT Press, 1989.

[4] AP164: Ábalos & Herreros. Selected by Kersten Geers and David Van Severen, Juan José Castellón González, Florian Idenburg and Jing Liu, with an interpretation in photographs by Stefano Graziani, Canadian Center for Architecture-Park Books, Montreal-Zurich, 2016.

Images:

- Architecture and Its Image: Four Centuries of Architectural Representation, 1989.

- AP164: Ábalos & Herreros, 2016.